The Centre for Language and Speech Technology at Radboud University Nijmegen and the game company 8D collaborated to investigate the possibilities of speech technology within games that promote reading and speaking skills. During the project, the game concept and functional prototype DigiJuf was developed and tested at various stages with children in elementary schools.

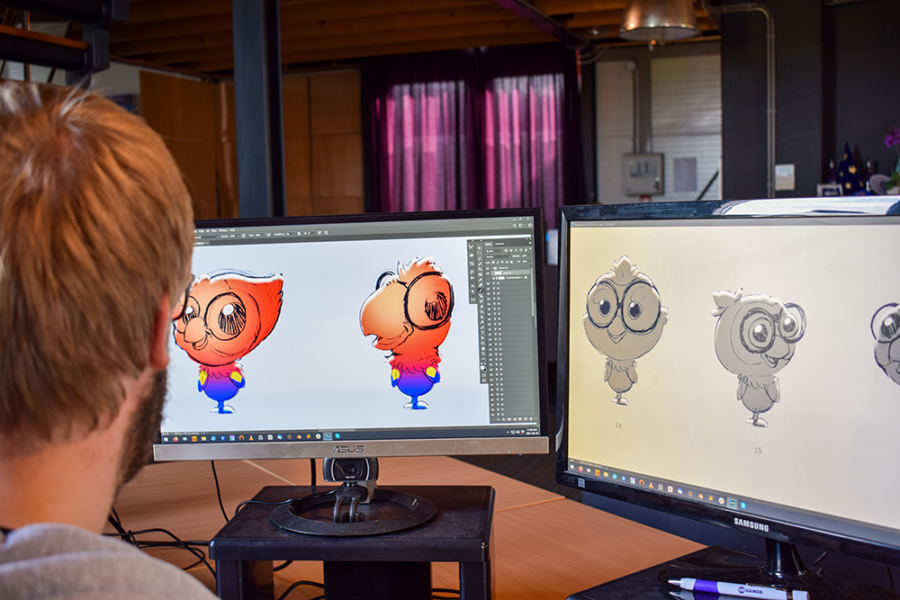

Automatic speech recognition technology is ideally suited for educational applications because it can be applied directly to the development of two fundamental skills in children’s education: speaking and reading. 8D and the Center for Language and Speech Technology (CLST) therefore worked together in recent years to develop a digital “language buddy. ‘Interviews revealed that children regret that reading is often done alone and that they have no influence on the course of the story,’ says Giel Hekkert, closely involved in the project from 8D Games. ‘That touches on an important principle from the gaming industry: people are generally more motivated to do a task when they experience autonomy.’ So the idea was born to have children take turns speaking sentences on the smartphone and thus have them create a story together: each spoken message is converted live to text. In the process, of course, you have to read your classmates’ contributions carefully to add a new twist to the story yourself. Players are instructed to incorporate certain words or phrases into their contribution and can then vote for the best fragment.

Speech technology from CLST

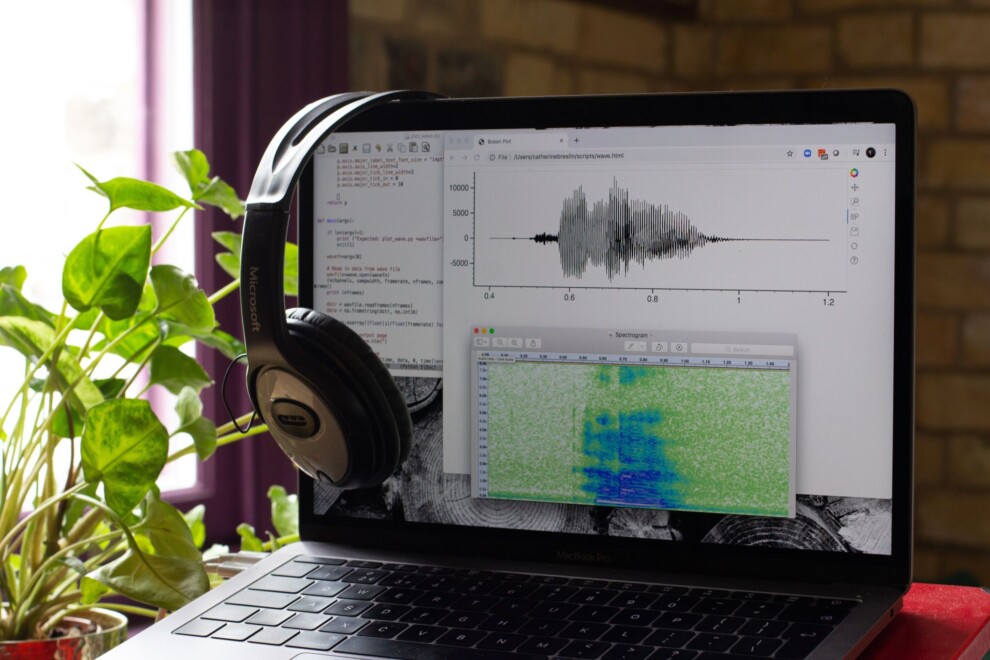

Researchers at the Centre for Language and Speech Technology (CLST) at Radboud University Nijmegen developed the speech technology for the game. ‘We are currently doing several projects in the field of reading and spelling and each application requires its own technology,’ explains Helmer Strik of CLST. ‘In standard speech recognition, speech is converted to text. In the case of DigiJuf, the speech recognizer must additionally be able to assess whether the words are pronounced correctly by the child. Speech recognition of children is difficult anyway because of the wide variation and pitch of their voices. If you then limit yourself to reading predetermined sentences it is easier, but at DigiJuf the children were given a lot of freedom. In this project we worked on optimizing speech recognition for that.’

Testing in elementary schools

An initial prototype was tested with over forty elementary school students. Hekkert: ‘During these tests we once again tested the creative concept and – in a technical sense – mapped out how CLST’s speech technology can add as much value as possible in a game like this. What was nice to see: children started speaking differently after only four sentences. Thus, they started to articulate better in order to see their contribution to the story appear as good as possible in the game. We also saw that this game form stimulates creativity and involves a lot of fun, making children forget that they are actually practicing reading and speaking.’

The data from the test phases was analyzed by Strik and his CLST colleagues, and the results were in turn used to improve the prototype. In addition, they examined how children rated the pronunciation of their peers, compared to adults and the ASR system. Strik: “Previous studies show that getting feedback from peers has all kinds of benefits, such as increasing engagement and learning to think critically. Our research shows that children are just as reliable assessors as adults. That means that elementary school-aged children can provide feedback that is suitable to complement DigiJuf’s feedback.’